In Bloom: A Review of Jessy Randall’s ‘How to Tell If You Are Human: An Illustrated Addendum to Nirvana’s “Nevermind”’

By Paul David Adkins

Posted on

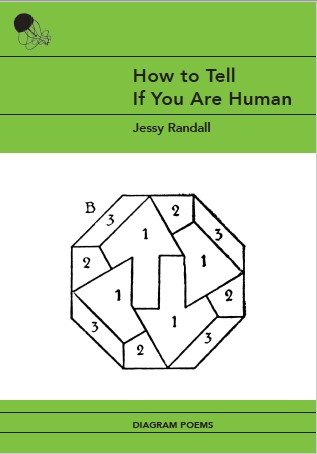

Jessy Randall’s 2018 poetry release How to Tell If You Are Human contains 29 black-and-white, grayscale, or full-color diagram poems, encompassing a dizzying range of personal experiences. By calmly exploring and analyzing mental illness, isolation, and multiple facets of human relationships, Randall’s speaker helps to raise our understanding of the bewildering set of interactions a person must navigate on a daily basis to function in American society. Commendably, she accomplishes these observations, all the while touching upon the spirit of the iconic 1990s Nirvana album Nevermind. In a brief 78 pages of verse, observations, and illustrations, the reader is left with a humming sense of his own disconnected state, coupled with the realization that this unique predicament is universal and, in fact, entirely disconcerting.

How to Tell If You Are Human is divided into three parts: “They Finally Figured Out What’s Wrong With You,” “How to Tell If You Are Human,” and “Be Yourself (But Not Too Much).” The opening piece (all are untitled), centered above a response-focused bar graph, resembles a question found on a psychological evaluation test, only much more involved, specific, and disturbingly personal. As the reader examines the piece, he is actually faced with a series of three questions, concluding with a declaration: “And then you’ll have an argument and the band will break up all because of your vanity.” Immediately, the speaker sets the tone, placing the emphasis on anxiety, how this disorder naturally unhinges its sufferers from logic and wellbeing.

Nirvana’s song “Territorial Pissings” provides an accurate musical accompaniment to Randall’s collection. Kurt Cobain’s lyrically jagged chorus (“Gotta find a way, to find a way, when I’m there // Gotta find a way, a better way, I’d better wait”) perfectly encapsulates Randall’s poetic vision. Cobain’s line “I’d better wait,” given the songwriter’s own deep-seated insecurities, chillingly reflects page 9’s image of two clinching boxers standing in separate barrels: one whispers, “I love you / so much,” while the other warns, “Shhhhh.”

There is a self-defeating ring to understanding the need to escape a situation while simultaneously acknowledging its impossibility, explored by Nirvana in Nevermind, which Randall’s speaker reiterates throughout the collection. Page 31 contains a color photograph of a starfish with two stanzas: “I should probably / get going // please / ask me to stay.” This ambiguity reflects well in the lyrics of Cobain’s “Drain You:” “I don’t care what you think unless it is about me / It is now my duty to completely drain you.” Meanwhile, the diagram poem on page 5, displaying two almost identical house floor plans, reads in the first image, “the way I felt about you then.” The second, which adds a flight of stairs and slight modifications to the original plan, states, “the way I feel about you now.”

While “Drain You” examined Cobain’s romantic-then-platonic relationship with Bikini Kill drummer Tobi Vail, Randall’s speaker introduces that focus to individual readers. On page 43, accompanied by a series of four crudely drawn, modified ocean shelves, the verse reads, “FIG. 36. Slowly, inexorably, over many years of conversations / and travels, they revealed their true natures. By the / time they knew all each other’s flaws, it was too late / for them to stop being friends.” In a beautifully illustrated, dual-paged diagram poem on pages 46-47, the speaker uses colored drawings of anatomically correct beetles to mimic Valentine’s Day candy hearts, with messages such as “you seem adventurous,” “mm-mmm / delicious,” and “are you into / erotica.” This connection between sexuality and entomology compares well with Nirvana’s own struggles regarding self-identity and -loathing. In the 90s youth anthem “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” Cobain’s lyrics similarly confessed to inhabiting a body which was simultaneously abhorrent and nevertheless habitable: “I’m worst at what I do best / And for this gift I feel blessed.”

Part Three of Randall’s collection examines the awkwardness accompanying existence in modern America. The speaker claims on page 63, amid the diagram of a library, “In regular life / I talk too much // but in a poem I can be // perfect.” She addresses similar conflicts on page 64 when she writes within the confines of a drawing of a school and playground, “all day long / we looked / out the / windows // and then at recess / we looked at each other.” In Nirvana’s composition “Come as You Are,” the lyricist addressed similar issues regarding the complexity of interactions, writing “Take your time / Hurry up / The choice is yours / Don’t be late.” The indecision populating the song reflects precisely what Randall’s speaker repeatedly divulges to her readership, lines which could have been directly penned by Cobain: “be yourself / (but not too much)” (67).

As Randall’s speaker closes the collection, she faces the fact that she cannot extricate herself from her inability to personally connect with others. The poem on page 72, bracketing an intricate diagram of a mechanical comb, reads, “When I saw you / I wanted to race / over and give you / a hug but I resisted / the impulse // I don’t know why.” Nirvana confronted the same confusion in their song “In Bloom,” where the songwriter composed “Sell the kids for food / Weather changes moods.” In both poetry collection and album, the reigning thought is that human connection, highly sought, is even more highly elusive. Randall’s closing poem employs the image of four realistic jellyfish. On the bell of each creature, the speaker writes a single verse: “I exist,” “so do I,” “ok good,” “that’s settled.” The animals exist within their own capsules, and the most they can muster in the way of commonality is to acknowledge their existence to each other. The most they can muster is . . . nevermind.

– Paul David Adkins