‘If You Come’ – A Reflection on Elena Ferrante’s ‘Neapolitan Novels’

By Tara Awate

Posted on

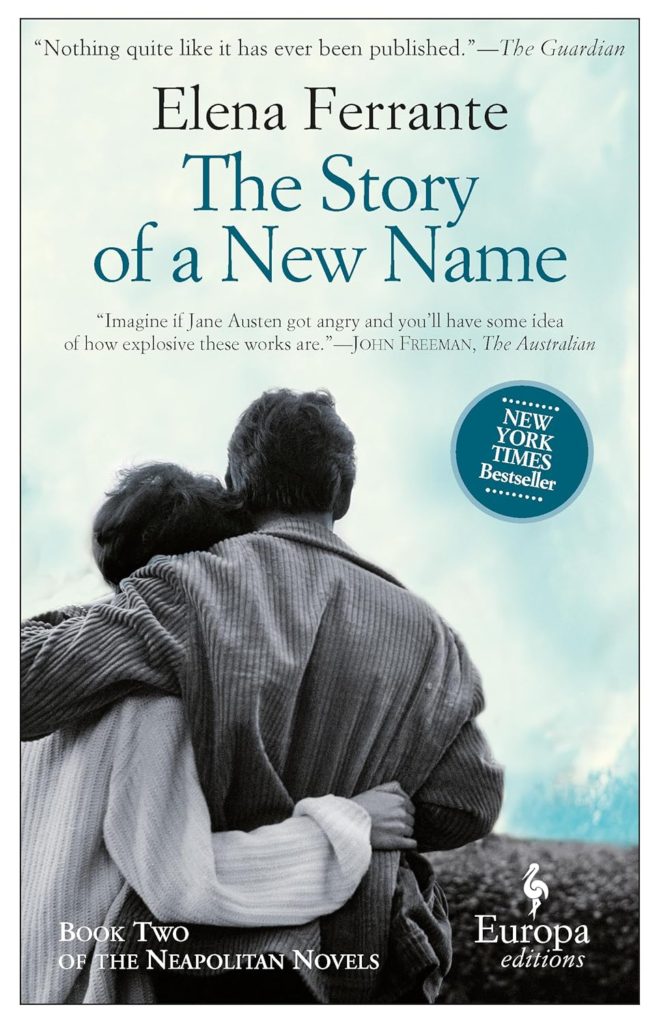

It was almost two am. I was in the common room of my college dorm, reading The Story of a New Name, the second book in Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan series. It was Saturday; I had given up a night of partying and fun with friends to sit alone and read. Three of my friends came in and I was so engrossed in the book that I didn’t notice until they were a foot away from me. Two of them were visibly tipsy, eyes narrowed by tiredness. K leaned in and hugged me, relaxing all her body weight onto my shoulders, limbs loosening into sleep.

“Okay let’s go” the other two said and hoisted K up from me.

“Get high with that yet?” one of them says, looking at the battered copy lying in my lap.

“I already am”, I said with a laugh.

I picked up the book after I read on the blurb, “Elena Ferrante’s piercingly honest portrait of two girls’ path into womanhood.” I was in a state of transition myself, having moved to college, and a coming-of-age novel full of growing pains and angst was just what I needed. Ferrante’s writing had a seriousness to it. It was unembellished and easy to read but was a far cry from any other young adult novel I’d read. I couldn’t stop reading it in whatever spare time I got between classes.

Sitting in the common room, I came across the paragraph where the protagonist, Lenu says of her friend Lila, “The more her mind was ignited as, in minute detail, she planned how to make every part of the ruse add up, the more skilfully she ignited mine, too, and she hugged me, begged me. Here was a new adventure, together.”

I put the book down for a moment, a moment that turned into an hour during which, memories I’d stuffed away came flooding back. The dam was let open now and soon, the tears came too. I’m glad there was no one around me.

Reading that exchange and all the unsaid things between Lila and Lenu, reminded me of the conversation I’d had with my own estranged best friend, P a year ago. It had been 5 months since we’d last spoken and by then, I’d begun to look at her through rose-tinted glasses. I sometimes harboured thoughts of running into her accidentally when I’d be back in my hometown. Then after some initial awkwardness we’d slip back into our old selves and talk like no time had passed.

Now I was wide awake as though a shock had jolted through me and brought me to my senses. That one sentence conjured up my own friend for me, unfiltered and in entirety, whom I loved and despised.

Exactly a year ago, P had called me and said, “Do you wanna go on a trek this December?” I thought, Really? That sounds so fun! After so long. I tried to tone down the excitement in my voice and didn’t say these exact words. That didn’t sound like her and sounded too good to be true. And it was. Of course, her boyfriend, S, was coming too.

When she invited me, I was busy with my college applications. I’d be out of the country to go to college in a few months. She’d moved cities two years ago and we had maintained regular contact through chatty, rambling phone calls during which we talked about everything under the sun. In the beginning, she’d often mention a guy in her class, S, trying to convince herself and me that she most certainly did not like him. We’d fallen out of touch since she’d started dating S and our friendship was strained, partly owing to my sporadic confrontations about her abandoning me, not returning my calls. Going on this trip with her would be a much-needed reconciliation. Not quite a return to the old times but I hoped we’d redefine our friendship and its dynamics and I’d meet and try to befriend S.

In the book, a married Lila pursues Nino– Lenu’s infatuation– during their beach vacation (to which, ironically, Lenu had dragged Lila along to be close to Nino) and they start an impassioned, illicit affair. She needs to go behind her mother’s back to meet Nino and she asks Lenu to come with her so that her mother will relent to letting her stay at their friend’s place for two nights.

P said on the phone, “There’s kinda a problem…. mom’s not given me a full yes yet. She doesn’t trust me, after what happened with him.” The him here wasn’t S but another guy who was pursuing her a year ago, on whose motorcycle she’d ridden away in the evening, to another city. Her parents had no clue. He took her to his empty flat and things quickly got out of control.

“But when I told her you were coming, she said yes”.

“If I’m there, she’ll allow?” I said.

“Oh for sure. No doubt.”

My first thought was that she was tagging me along, cause otherwise she wouldn’t be allowed to go. I was supposed to act as her chaperone and I felt disposable, a third wheel. But when she said this so affirmingly, that her mom would only allow her if I was there, welled something in me, warmed me.

Our friendship went way back. Her family knew me for eight years and had really warmed up to me. In seventh grade, her parents had driven me in their car to her grandparent’s house in another city to spend a short vacation with her. She’d told me to bring floating paper lanterns to fly for Diwali and we’d been planning to light them since weeks. When I did, she, in a show of her usual unpredictability of mood, stayed cooped up in her room while I went to the main terrace of their house. Her grandma waved at me from below. I released the lit lantern into the warm autumn sky and saw the lone light bob and drift along in the dark, until it disappeared.

The erratic and capricious behaviour that Lila displays, I had seen in P over the years. Looking back, her mother probably saw me as a very sensible and level-headed girl, plain in places P was jagged. She must have hoped I’d have a desexualising effect on her during the trip. I was the most sexless teenage girl she’d have come across, with my indifference, my thick glasses that obscured my entire face and the way I dressed. I never tried to be anything else, didn’t think I could be. I’d been perceived that way all along and then subconsciously boxed myself into that persona.

Time and again, whatever Lila did, took on an importance and made Elena feel she was missing out. Lila could imbue anything with grandeur by talking about it fervently, even if it was just a small labour-driven shoe factory.

After Lila gets into an abusive marriage, her husband forces her to bear him children. After many months and one miscarriage, she still isn’t pregnant. Her husband and his sister say that she’s a witch; there’s an evil force inside her that’s killing all the babies in her womb, not letting them grow. Lila confirms for Lenu her sister-in-law’s accusation—that Lila has the ability to not get pregnant, and if she was unsuccessful she would let the child drain out, rejecting the gifts of the Lord.

P emailed me a meticulously hand-written ten-page itinerary of the trip. I remembered that distinctive, cursive handwriting I’d known since fifth grade— the alphabets a bit too elongated and a bit too thin, like I was. It had only slightly changed since then. No one wrote like that in our class.

She then emailed me a google meet invite link, saying it was to get together to discuss the itinerary for the trip. I noticed I was bcc’d. I couldn’t show up because of work. When I asked her later how the meeting went, she said it didn’t happen. I asked why. Cause I was waiting and you didn’t show up, she said. Only S did and he didn’t need a whole presentation– they both had come up with the itinerary together, complete with room accommodations and planned slots in their schedule for regular fucking. She would later reveal this to me indirectly and bashfully. In the earnest, childlike curlicues of her handwriting, I still saw an innocent, clueless middle-schooler. And I couldn’t reconcile these two images.

I was told we would be living in tents for most of the trek. But she’d convinced her parents to let her book a hotel room for one night, for both of us, under her name and mine. She asked me if I’d be okay sleeping out of the room for that night, on a couch in the hotel lobby, so that she and S could be alone.

By sending a meeting link and handwriting a finalised ten page schedule in which I had no say, she made the briefing for the trip seem like a big, official event when it actually wasn’t. To very subtly hint that I was just one among her many friends who would volunteer to come on the trip with her in a heartbeat, even if I didn’t. When in reality, she just had S, no one else. Through such minute details, she’d manipulate the situation in a way that showed her power. By fine-tuning her words and slightly twisting them, she could create the impression she wanted to and elicit a desired reaction from people.

After Lila visits the doctor twice, Lenu realises that she is unable to conceive because she is weak and needs to get strong, not because of some malignant power inside her. The shroud of witchcraft around Lila falls away to reveal a waifish figure.

Once, meeting in her apartment’s parking lot, P had me questioning whether one of my friends was really my friend at all. Without exactly back-biting her, P spun a narrative out of existing facts and events, that caricatured her to seem like an opportunistic person who was using me and didn’t really value me. And for my future peace of mind, it’d be better if I acknowledged this now. I knew that the friend in question was genuine, the way one just knows, and I defended her. Still, I was short for words to hold my stand because P made some of her claims against my friend seem plausible by sheer invention of dishonourable intentions I’d overlooked in the friend. She used her words with an awareness of their malleability and tone, hitting all the right spots.

I was aggravated at her resolve, at her sheer persistence in convincing me of that friend’s unreliability and fakeness, but at the same time found myself believing her. I’m still good friends with that person but I haven’t spoken to P in months.

Only one letter separates friend and fiend. Lila made that one letter difference seem paltry and jumped that r often. She could be manipulative and similarly bend their shared reality and distort it to her advantage. Lila never broaches the subject of Nino with Lenu, never ensures that Lenu’s fine with her being with him. Lenu had never openly admitted to Lila about her love for Nino but it must have been obvious to her. Initially, Lenu doesn’t concede to the fact that Lila has taken Nino away from her. She internalises what Lila indirectly but consistently implies through her actions: that Nino never even liked her, the way their liaison is progressing, he was Lila’s to have all along and how could it be any other way. In one effortless sweep, Lila completely erases from Lenu’s mind her previous flirtations with Nino, any indications that he liked her. Lila changes Lenu’s perception of events and people, not even giving her space to feel indignated.

After a while, when Lenu realises that she hadn’t just imagined it and there had been something between her and Nino but Lila had without remorse snatched it away, she feels acute pain and distances herself from Lila– an estrangement that spans many years of their young adult life.

Their friendship is fraught with envy, betrayal and spitefulness but in the end they always gravitate toward each other. At the core there is love and all these feelings spring up from that same well. In their neighbourhood there was no one who understood them better than they did each other, no one to look up to except each other. All through school, P had stood up for me when no one did, noticed and believed in things no one did. We were part of our own little world and didn’t need much else to have a good time.

I found myself nodding when Lenu grows nostalgic, saying, “I still think that much of the pleasure of those days was derived from the resetting of the conditions of her, or our, life, from the capacity we had to lift ourselves above ourselves, to isolate ourselves in a pure and simple fulfilment.”

A few days into discussing the winter gear we’d need during the trek, we conspired to invite my high school crush on the trip, without him knowing that I’d be there. And when he saw me, he’d be surprised. Recently, he had made a few attempts to reconcile with me, as though that was even possible. My infatuation turned mortal enemy. He had been a total jerk once upon a time and I’d resolved to never meet him. Upon this, she said that’s exactly why I’m gonna invite him on the trip. We were gonna put him in his place. We planned that I’d try to seduce him and get him to fall for me. I’d make out with him and then make a fool of him. We’d get him to apologise to me on his own for all that he’d done so many years ago. And P would be witness to this, as she was witness to that four years ago. We decided she would pop in at opportune times to guilt trip him when it’d hurt the most. I would act unyielding and distant and he’d trail behind me, full of puppy love, repenting his actions from over four years ago. The power dynamic would shift and the roles would be reversed. How full circle it would be.

For me, it wasn’t about him. I had stopped caring about petty high school rivalries. I think what excited me was that P and I would orchestrate the whole thing together. I’d aid her in deceiving her parents about her intentions for the trip, we would hatch a plan to put to shame the most popular guy in our high school. It would be a project. It’d be like old times, something we created together, our own, exclusive expansive world. Like our nerdy book fandom that no one got, our inside jokes, skipping class after lunch break to go sit in the library, her sweet-talking our way past the sour-faced librarian. By planning a charade to get close to him, I found I was growing close to her again.

Long after Lila is married, Lenu still echoes this feeling: “Lila knew how to draw me in. And I was unable to resist. I was depressed at the idea of not being part of her life. The two of us together, allied with each other, in the struggle against all.”

I put down the phone after we had giggled and guffawed like we used to two years ago. I felt for a moment that our old selves had taken root within us again, that something vital was restored. We were role-playing those coy girls in teen rom-coms, plotting how to play silly mind games on a boy and then break his heart, all drawing from our newfound wellsprings of feminine charm. Then something I’d known along, swiftly presented itself with resounding clarity: I could only relate with her by talking about a guy. This had been our most exalted conversation in weeks (months?), with her fully invested and perked up. However much I’d enjoyed it and added to it myself, the fact remained: the Bechdel test was out the window.

I was only playing out the girl from the rom-com but she had actually become her.

If tomorrow I went to her and started crying because a guy had broken my heart or because I was having boy problems, she’d put up with all of that willingly and console me. Any other problem I cried over just couldn’t be as hurtful, couldn’t have that gravity. Romantic love trumped everything else for her and she would keep demonstrating that to me again and again. This was the only language she spoke best now. And if I didn’t speak it, we could be friends but there’d always be a rift.

Later, when I discovered that I had an application deadline during the days she had planned the trip, I asked her if we could move the dates. The schedule was written in ink—she gave several reasons why we couldn’t: S started college two weeks after that. Her mom would change her mind. The snow would thaw by then. It wouldn’t be as fun. Then I gave her several reasons why I couldn’t come. And that was that.

My phone beeps. It’s 3:15 am now. There’s a text from K. I’m bored n I can’t sleep. Wanna come over?

I pack all my stuff and text back, Coming.

– Tara Awate