Summer Samaritan

By Mark Hendrickson

Posted on

Little David—ti Davíd—was late for his own funeral; but you can hardly blame a three-year-old. People shuffled back and forth, antsy to get things moving. We were on the clock. The day, like all days, was hot and cloudless; and since there was no embalming here, the child needed to be buried before sundown.

The boy had been brought by his father to the only hospital on the Haitian island of La Gonave. It was only open for a few weeks if and when the American doctors could come for their annual mission. That year there was enough of a lull in the nation’s seemingly endless string of turmoil and bad luck that they were able to make the trip.

The doctors brought with them a group of high school students for a short musical mission, a sort of side gig. I was a college student at the time, studying music, so I volunteered to be one of the music group’s leaders. When everyone else departed, the local missionary leader there allowed me to stay on for the rest of the summer (for a small donation). I thought I could observe, maybe get some college credits for it; be a kind of tourist missionary, a summer Samaritan.

By the time ti David got to the hospital he was already at death’s door. He suffered from dehydration, malnutrition, tapeworms or some other type of parasite, diarrhea: the list went on. The doctors tried valiantly, but every time they tried to solve one problem, it exacerbated another.

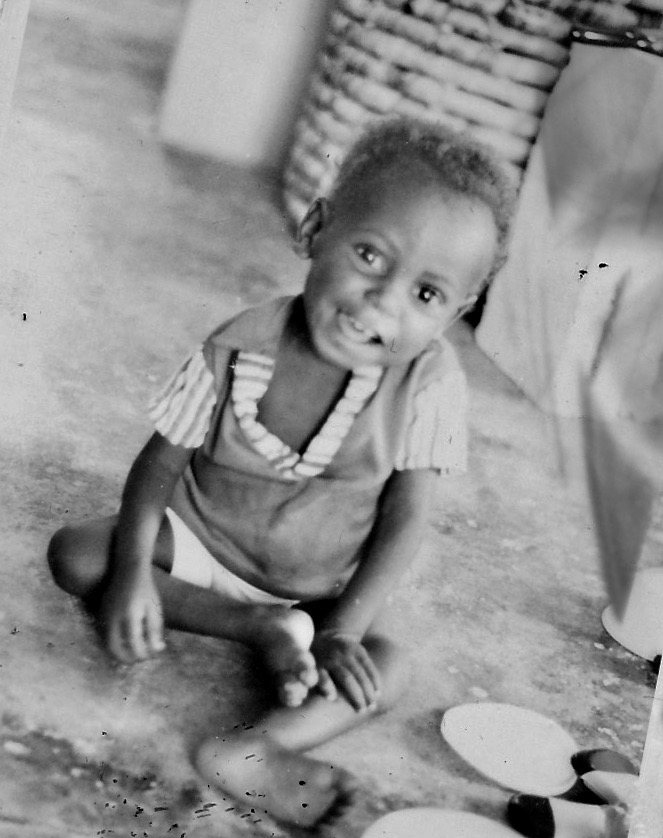

Then one day he seemed to rally. When I came to visit him at the hospital he was up and sitting up in the corner on the dirt floor, legs akimbo. I rolled a small ball to him and watched it pass between his feet and bounce from emaciated shin to wasted thigh, like human pinball. He smiled. The missionary lady working there happened to take a picture at that moment. She gave me the Polaroid. His father said it was the only time in his life the child had ever cracked a smile.

But it was only a feint, as if he had only lived for that moment; and perhaps he had. His health declined rapidly from that point: the point at which I became prayer. I prayed that he would live. I prayed that God would take me instead. I prayed until it felt like weeping blood. This must be what it is like to taste motherhood, and it calloused my knees. In the end, I prayed that he could die and be spared his suffering. After what seemed like an endless period of suffering, he did, with no help from anyone.

Now all there was to do was to wait impatiently for the funeral to start. I could hear the child’s father arguing with the carpenter over the price of constructing his child’s coffin. The carpenter refused to finish the coffin until he was paid, but his father simply couldn’t afford to bury this last child after just burying the rest of his family—recently. I wondered how often Jesus must have heard arguments just like this. Plywood, nails, and paint can be a heavy death tax.

In the end, I joined some of the missionaries who reluctantly (and quietly) palmed the carpenter a few centimes each, and the price was paid. It set a bad precedent: if you do it for one, soon you will have to do it for everybody. It felt like giving coins to Charon to ferry a soul over the river Styx. I had been naïve enough to think kids three and under rode for free.

Children’s coffins are always too white, like veneers over rotting teeth. Pioneering flies were busy trying to claim homestead in the tear ducts of the child’s body, trying to get in one more drink before last call. The casket was finally nailed shut, trapping the blood flies inside with the body. Somehow I found this quite disturbing, then found myself wondering why I found this so disturbing. Women began ritual wailing. Two men lifted the light casket up on their shoulders (though one would have been more than enough), and slowly…slowly…the funeral march began down the one main road through the village.

I could hardly hear myself weeping over the sound of flip-flops on dirt. Practically the whole village was there for the funeral, as they were for every funeral. No one else attended from our missionary compound (I was there, but I didn’t really count being more of a temp). The procession continued until it came to a sudden confused halt. There in the exact center of the road was a square of bright polyethylene netting surrounding four rods of rebar, only two feet square but five feet high, poking up like a garish plastic standing-stone right in the middle of the one and only street in the town. The Home Depot orange was startling in that otherwise dun setting: I knew of nothing else on the entire island with a color like that. The netting guarded a small patch of dirt ground, and nothing else. The men carrying the coffin nearly dropped it as each struggled to go around the obstacle in opposite directions.

The town square, as I called it, was claimed by both missionary compounds: ours, and those other missionaries three blocks away who no one would introduce me to. The ongoing dispute between them over the ownership of this nothing was bitter; and like any two churches across the street from each other in any small town back home, both sides now refused to talk to the other, leaving the hazard standing there like an orange finger flipping everyone off. No one could explain to me what either side could possibly do with such a space should they succeed in claiming it. The people in the procession seemed more resigned than angry about this, quite used to having no say in matters affecting their everyday lives. I felt ashamed that the child had to detour around the Church on his way to heaven. After a few moments of awkward jostling, the men managed to stabilize the coffin, and the congregation continued to the cemetery at the other end of the village.

It was my first funeral since arriving in Haiti. I don’t know what I was expecting the cemetery to be like, but I knew going in that bodies would be buried above ground. Perhaps I had a vision of mausoleums or sepulchers or solid stone slabs like we had back home in America. This was nothing like that. This was chalk and rubble, like the set of the Flintstones. Gray as a moonscape: blasted concrete, stone, and gravel was heaped all around in disordered piles. No one could imagine a blade of grass ever growing there.

The small white casket was laid on the gravel with care, and people started piling up rocks on top, by hand, until the box was covered. Everyone became blanketed in white concrete dust and chalk. One small rock, smaller than my fist, was placed loosely on top of the others as a marker. It was painted forget-me-not blue.

Since I had arrived as part of the musical mission, I still had my trumpet. ti Davíd’s father asked me to play at the funeral. My trumpet was a Bach Stradivarius of pure sterling silver, cold and gleaming in the harsh sunlight. I wondered how long anyone there would have had to work just to make what I paid to get it out of customs. I saw my reflection in the bell, distorted: a portrait of Dorian Grey in silver. Argent, I decided, was the true color of entitlement.

Naturally, they asked me to play Amazing Grace. Everyone always asks for fucking Amazing Grace. I was crying, and my lips were trembling. Knowing that small boy had suffered his entire young life, then watching him die such a painful death; knowing he would still be alive if he had just been born somewhere else; knowing he never had a single chance, while I stood there with my silver trumpet; I could find no grace. But it was the only tribute I could offer him, or his father. I sobbed my way through it by pretending I was a soldier playing TAPS: which, if you analyze it, is basically the same song with the same notes in the same order. The funeral ended and I wondered who besides me would ever remember him. I didn’t even know his last name.

I walked the father back to his house—a small hut made of corrugated tin (about the size of my bathroom back home) where five people used to sleep—then left to meet some of the other missionaries for a drink. My job was to cut up the pineapple for daiquiris.

They all lifted their glasses to the boy’s father and toasted, ‘Dead man walking.’ Never having heard that term before, I asked what they meant. They explained that within minutes the whole community would descend on the child’s father at his little house to celebrate the life of his child. As per tradition, they would celebrate every night for one week; and as expected he would feed and entertain the entire crowd, spending the very last of his money, and giving them the very last of his food. Then, when the week was over and he was finally left to mourn alone, he would inevitably starve to death.

I asked if there wasn’t something we could do to intervene. They told me it was not our place to interfere in the religion, culture, and traditions of the people there. I left, asking if that wasn’t the very definition of the word “missionary.”

Soon the summer was over, and I left the island to go back to studying music at college, where I wore my tuxedo and played Baroque music on my silver trumpet at churches for the holidays. After that I went to seminary but left the ministry after eight months. Later, I sold my trumpet cheap to a visiting performer from Mexico.

Now I sit and write, and I remember ti Davíd. I have the photograph of him, with his one-and-only smile, in an album in a box in my closet. I no longer play any instrument, and I no longer pray—except at those times when I am so frightened that I forget I don’t believe they are answered. I look in the mirror I still see that twisted reflection, older. And whenever I hear Amazing Grace my mouth still goes dry as chalk.

Author’s Note: “Summer Samaritan” was written about a short-term missionary experience on the island of La Gonave, Haiti in 1982. I was a white, sheltered, entitled trust-fund kid with no knowledge or understanding of colonialism or my role in it. The events in the story are true.