Sgt. Pepper at 50: What Can Writers Learn?

By Philip Ivory

Posted on

“I’d love to turn you on.”

AN EXPLOSION OF POSSIBILITIES

In the early 70s, a little after my 10th birthday, I sifted through my parents’ stacks of 50s and 60s Broadway musicals (South Pacific, My Fair Lady), James Bond soundtrack LPs, comedy albums (Bob Newhart and Beyond the Fringe), and one-off oddities like God Bless Tiny Tim.

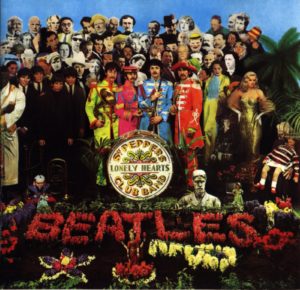

In that stack was Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Putting aside my childhood fear that rock and roll was somehow scary or indecent, I put the record on the turntable and gazed at the densely packed cover.

I was intrigued by the faux-audience sounds that accompanied the title track; moved by the communal sympathy of “With A Little Help from My Friends”; captivated by the throwback music hall charm of “When I’m Sixty-Four,” and transported by the visionary landscapes that unfolded in “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” “Being for the Benefit of Mister Kite,” and “A Day in the Life.” Having grown up on Lewis Carrol, I found the fantasy elements to be welcoming, familiar. But the doom-laden orchestral rush on the latter track frankly scared me, making me wish I’d chosen to listen when my parents were home.

But there was no turning back. Clearly, rock and roll was about more even than the groove of “Satisfaction” or the bitterness of “Like A Rolling Stone.” Sgt. Pepper spoke to me in a way no album has ever since.

“We were changing our method of working at that time, and instead of now looking for catchy singles, it was more like writing your novel,” Paul McCartney said.

It’s been suggested that, when the Beatles settled down in late 1966 to create a new album, their intent was to explore the theme of childhood. Two of the first tracks produced, “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane,” evoked childhood memories of actual Liverpool locations, seen through a hazy psychedelic lens. However, to bridge the long gap since the release of their previous album, Revolver, the two songs were plucked to serve as an interim single, losing their place on the album and opening it up to new directions.

Clearly, the Beatles were thinking in thematic terms, open to a more literary approach to crafting their material. “Writing your novel” as McCartney remembers it.

It was an attitude that embraced possibilities. Rock and roll could be anything you imagined or wanted it to be. A boat ride with Lewis Carroll and Alice on an hallucinogenic Thames. An afternoon spent marveling at the circus or flirting with a meter maid. Heady inward-looking mind trips about “fixing a hole where the rain gets in,” or discovering that “you’re really only very small, and life goes on within you and without you.”

Sgt. Pepper was playful with form, its songs flowing into each other like dreams. Side Two could point over its shoulder to something on Side One. Mysterious murmurs and bursts of laughter made the listener complicit in adding imaginative touches to the Beatles’ immersive soundscape.

As reviewer William Mann put it at the time: “Any of these songs is more genuinely creative than anything currently to be heard on pop radio stations, but in relationship to what other groups have been doing lately Sgt. Pepper is chiefly significant as constructive criticism, a sort of pop music master class.”

Sgt. Pepper still stands, at the very least, as an explosive statement about creative possibilities.

“I’m changing my scene, and doing the best that I can.”

PROGRESSING CONSTANTLY

The Beatles labored for many months on Sgt. Pepper, working in secret, sparing no expense.

In contrast, their first UK album, Please Please Me, largely a document of their early stage act, was mostly recorded in a single day and issued soon after in 1963. It’s astonishing to listen to 1967’s Sgt. Pepper and contemplate how far the group had come, not only in their growing melodicism and lyrical sophistication, but also in the use of innovative production techniques, with the help of peerless producer George Martin.

By the release of Revolver in 1966, the group had broadened their subject matter from teenage love and despair to yellow submarines, tax problems and, in “Eleanor Rigby,” the scourge of loneliness. (A subject that would be revisited in Sgt. Pepper, even reflected in its title.)

The Beatles’ musical progressivism allowed for invigorating influences like George Harrison’s embrace of Indian music and McCartney’s immersion in the mid-60s avant-garde scene in London. Competitiveness with their rivals played a factor as well. Knocked out as the Beatles were by the Beach Boy’s Pet Sounds LP in 1966, they hoped they could do better.

James Joyce only published four major works in his lifetime, providing an example of startling progressive growth in the literary world. Advancing from his short story collection Dubliners through Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Ulysses, and Finnegans Wake, each book seemed to grow exponentially from the one before in technique and structural innovation, somewhat in the way each Beatle album in the mid-60s came to be anticipated as something new and startling.

(In a 1968 interview, Lennon acknowledged having dipped into Finnegans Wake, finding Joyce to be “an old friend,” but admitted to giving up after a single chapter.)

In 1966, the Beatles’ artistic growth brought them to a crossroads. The punishing schedule of live performance all over the globe had become untenable. Death threats and other problems on the road played a role, but the Beatles’ chief complaint was that they were playing badly due to the shrieking throngs that made it impossible for the band to hear themselves. Also, as musical arrangements and production layering became more intricate on albums like Revolver, there was simply no hope of faithfully reproducing many of their new songs live on stage.

Because live performance was part and parcel of the group’s image and considered essential to the business of selling records, the group’s move to leave touring behind forever was a traumatic one. But as the poet Tennyson said, “Men may rise on stepping-stones of their dead selves to higher things.”

In a metaphoric mirroring of the Beatles’ conscious decision to reinvent themselves as a different kind of group, McCartney suggested they adopt, if only for the purposes of the upcoming album, the identity of the mythical Sgt. Pepper’s band,

“I thought it would be really interesting to actually take on the personas of this different band,” McCartney said. “So I had the idea of giving the Beatles alter egos simply to get a different approach.”

This assumed persona was simultaneously old and new, as exemplified by the title track which combines, on the one hand, old-fashioned show business clichés (“It’s wonderful to be here, it’s certainly a thrill”) and a horn section right out of an Edwardian Sunday afternoon concert with, on the other hand, some of the hottest, most stinging electric guitars sounds heretofore committed to vinyl.

The freedom this disguise provided can be seen in the extraordinary creativity and eclecticism of the album, ranging from old-time stuff your grandma could embrace (“When I’m Sixty-Four”) to Indian mysticism (“Within You, Without You”). Odd inspirations abounded. A painting by Lennon’s four-year-old son yielded “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” Newspaper stories helped fuel “She’s Leaving Home” and “A Day in the Life,” just as a Kellogg’s Cornflakes commercial gave birth to “Good Morning, Good Morning.”

“Do you need anybody?”

CRAFTING VOICES TO SUIT YOUR MATERIAL

I teach a creative writing class for The Writers Studio, a school that encourages students to try out different narrative voices, to be conscious of the crucial distinction between the author and the crafted voice, or persona, that’s been chosen to represent the material. That critical distinction separates the writer’s ego from the material. It also places a spotlight on the absolute necessity of maintaining the integrity of that persona voice to provide an immersive, rewarding experience for the reader. Readers, consciously or not, are aware of this integrity and abandon a story or poem if the persona voice becomes unwieldy or inconsistent.

In Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf, with extraordinary virtuosity, brings to life the complex sensibilities of a number of interrelated characters, diving deep in order to convey their innermost thoughts and depict their sensory experience of the world.

George Saunders’ 2017 novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, doesn’t delve as deeply but presents a greater number and variety of voices, as the thoughts of Abraham Lincoln and his recently departed son Willie vie with for our attention with distinctly-crafted voices of dozens of spirits who seem bound to the graveyard where Willie is being laid to rest.

In Sgt. Pepper, the Beatles indulge in a playful sense of experimentation when it comes to crafting various voices to serve the colorful array of songs, sometimes combining multiple voices of different sensibilities in one song. (This is seen perhaps most famously in “Getting Better,” when McCartney as the optimistic main narrator sings “It’s getting better all the time,” and is answered by Lennon’s muttering backing vocal: “It can’t get any worse.”)

Sgt. Pepper’s title track begins with a very excited “I” voice, that is, a first-person persona: “May I introduce to you/The act you’ve known for all these years.” It’s basically an emcee getting the proceeding rolling. The middle section of the song, however, presents the perspective of the band that’s been introduced: “We’re Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band/ We hope you will enjoy the show.” It’s still first-person, but instead of the singular “I” we now have a plural “we.” A small distinction but it means a two-minute song incorporates two different main voices. The use of multiple perspectives in this song and others lends them a filmic or dramatic quality, as if they were “scenes” as much as songs.

“With A Little Help from My Friends,” which flows directly from the introduction of singer Billy Shears at the end of the title song, continues this narrative playfulness. Shears turns out to be a sad and soulful first-person persona embodied by that most earth-bound and unassuming of Beatles, Ringo Starr. “What would you think if I sang out of tune/ Would you stand up and walk out on me?” His vulnerability and humility, after the electrifying excitement of the first track, puts us at ease and wins our sympathy.

The song, which seems to be about holding on in the face of loneliness, is deepened by the inclusion of supporting lines sung in question form by the other Beatles: “Are you sad because you’re on your own?” / ”What do you see when you turn out the light?” Again, there’s a dramatic quality that derives from multiple perspectives interacting.

“She’s Leaving Home” includes a main third person narrator sung by McCartney — “She goes downstairs to the kitchen clutching her handkerchief”— who gives us a detached perspective of this story of a teenage runaway. But emotional dimension is added through the emergence at three points of first-person lines from the perspective of the parents, delivered with shattering irony by Lennon: “We gave her everything money could buy.”

“Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” takes a different tack, drawing the listener right into its fantastical landscape by employing a “you” voice … “Picture yourself in a boat on a river.” “Good Morning, Good Morning,” uses a similar “you” perspective to place the listener into a more recognizable scene, a fairly drab stroll through a modern urban setting: “Heading for home, you start to roam, now you’re in town …” Both “Lucy” and “Good Morning” are cinematic in evoking unfolding scenes of a protagonist, with whom the listener is asked to identify, moving through a landscape.

Most ambitiously, the final track, “A Day in the Life,” offers two completely different first-person perspectives, pitting Lennon’s hauntingly disillusioned main vocal — “I read the news today, oh boy/About a lucky man who made the grade” — against McCartney’s more run-of-the-mill narrative about a guy drinking his tea and hurrying to catch the bus: “Woke up, fell out of bed, dragged a comb across my head.”

The lingering emotional effect of the song — what The Writers Studio would call mood — is made more complex by the juxtaposition of the two voices. Lennon’s section by itself, the first part to be composed, would have left us feeling melancholy and awed. McCartney’s bouncy mini-song, added later, offers a sense of reassuring ordinariness that gives way to unreality (“Somebody spoke and I went into a dream”). This adds coloration to Lennon’s grand melancholy, leaving the listener feeling devastated but also strangely exhilarated.

From the ominously bombastic narrator of “Being for the Benefit of Mister Kite” to the gentler, more humane tone of “With A Little Help from My Friends,” the Beatles show great agility throughout the album deploying a multiplicity of writerly voices.

“May I enquire discreetly?”

BEING AWARE OF TONE

Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” grabs us by the throat with the feverish tone of its agitated, obsessive first-person narrator: “TRUE! — nervous — very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad?”

Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, in contrast, is confessional, humorous and in-your-face conversational: “If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like …”

The difference highlighted here is tone, the surface texture and attitude of a piece. If you were to switch the tone of the two pieces, it would greatly affect the way that we, as readers, process the subject matter.

The Writers Studio urges students to be aware of both tone and mood (again, the emotional after-effect of a piece) and to consider maintaining a distinction between each in any particular piece. Adopting an unexpected tone — for one example, being cool about something that is odd or terrible or exciting — can lend dimension and vitality to the reader’s experience of the piece.

One of Sgt. Pepper’s songs, “Lovely Rita,” which is an ode to a meter maid, underwent an interesting tonal adjustment while being developed.

“This was about the time that parking meters were coming in,” McCartney, the song’s primary author, recalled. “I was thinking vaguely that it should be a hate song, but then I thought it would be better to love her.”

The narrator decides that descriptive details of Rita, from her little white book to her uniform and the bag across her shoulder that made her look “a little like a military man,” are worth loving, not hating.

Using the original tone McCartney mentioned, hating someone who hands out parking tickets, would have made “Rita” something of a tonal companion piece to the track that immediately follows, “Good Morning, Good Morning,” a harsh-toned meditation on urban life.

Embracing the “love” attitude instead lends “Rita” a kind of absurd jauntiness that is so good-natured — “Got the bill and Rita paid it, took her home and nearly made it” — that it wins us over and adds variety to the album’s emotional palette.

“In this way, Mr. K. will challenge the world!”

PAINTING ON A LARGER CANVAS

Many writers come to a point when they want to figure out if the smaller pieces can be made more meaningful by being placed in a larger context, whether it means shepherding poems into a cycle or expanding that fertile story idea to novel length.

Did the “novel” Paul McCartney spoke of come to pass? Is there a larger concept to Sgt. Pepper?

In truth, the concept of the mythical band who’ve been “going in and out of style” is prominent on only a few tracks. Lennon, whose justifiable pride in the Beatles legacy often vied with a desire to dismantle the mythos he’d worked so hard to create, later said that his songwriting contributions were not particularly related to the other songs or any larger Sgt. Pepper idea.

And yet, as others have noted, whether or not Sgt. Pepper is really a concept album, the structure and sequencing work extraordinarily well, creating a giddy eclectic rush as we hurdle from one heady musical environment to another. The effect is exhilarating. Maybe it doesn’t all mean anything. But it sure feels as if it does.

What is Sgt. Pepper about? It seems to me it has something to say about the loneliness and alienation of modern existence. At least six of the tracks deal, in one way or another, with the idea of loneliness, separation from others.

“We were talking about the space between us all …” sings George Harrison in ‘Within You, Without You,” opening Side Two and seemingly commenting on the proceedings thus far. The track expands the Beatles’ musical palette by combining Indian instruments with a traditional Western string backing.

Elsewhere on the album, the theme of aloneness is often juxtaposed against a desire for flight, escape into visions of fancy and wonder, leaving behind the drabness of “Going to work, don’t want to go” for the multi-hued fabulousness of “Cellophane flowers of yellow and green, towering over your head.”

Like James Joyce’s Dubliners stories whose themes are restated and enlarged upon in its majestic final story, “The Dead,” Sgt. Pepper culminates in its most ambitious track, one that seems to revisit the earlier themes of alienation and escapism, “A Day in the Life.” That this awe-inspiring final musical statement, with its haunting main vocal by Lennon, arrives at such a devastating crash-point with its orchestral climax and final apocalyptic chord, suggests that, in the Beatles’ vision, alienation and loss will win out over flights of fancy.

Post-Sgt. Pepper, the Beatles seemed to distance themselves from such lofty aims. By and large, their later albums, as brilliant as they often were, stand unashamedly as song collections, without any concerted attempt at a larger statement.

It’s still rewarding to contemplate the devices the band employed with such charm and facility. Shifting a song’s tone to provide a new lens on its subject. Creating little musical dramas by intertwining unique voices. Striking thematic notes to hint at a larger structure. We don’t know for sure how many of these ideas the Beatles pursued with deliberate artistic intent, or how many arose intuitively from a spirit of playful experimentation.

Visionary LPs by other artists followed, from Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars to Dark Side of the Moon and Thick as a Brick. Half a century on, the excitement of the Beatles achievement remains undiminished. It’s a safe bet that “the act you’ve known for all these years” will long fire imaginations, that the explosion of possibilities heard in ’67 will still reverberate within creative minds another fifty years down the road or more.