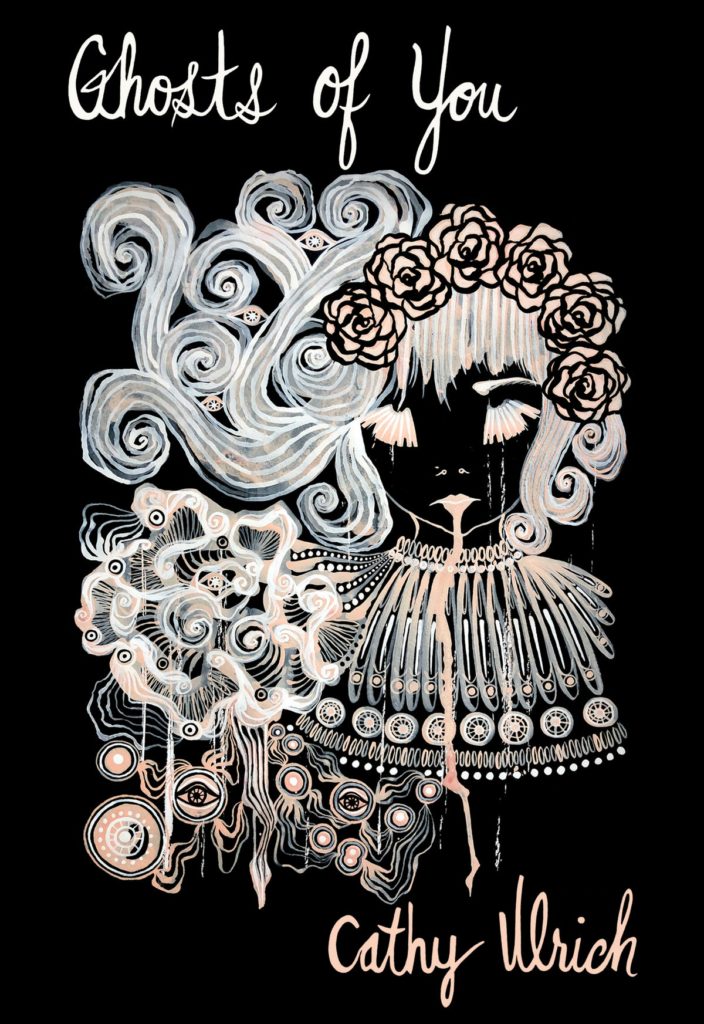

The Disposable Woman: A Review of Cathy Ulrich’s ‘Ghosts of You’

By Allison Wall

Posted on

I’ve been noticing a trend in movies: the inciting incident of the story is usually the murder of a female character. The more I thought about how many stories depend on a dead woman, the more disturbed I became. This story-starting device shows up over and over in pop culture, in films as diverse as Bambi, The Fugitive, Jaws, The Shawshank Redemption, Gladiator, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, and in every detective, police procedural, and true crime series, from Sherlock to Criminal Minds to 48 Hours.

Cathy Ulrich has also noticed this trend, and she wrote a book about it. Ghosts of You is a collection of thirty-one flash pieces from her Murdered Ladies Series. Each piece focuses on the tragedy of a different murdered woman, distinguished by their roles as given in the titles which all follow the format: “Being the Murdered [Role].” Roles include wife, cheerleader, and taxidermist. Each piece begins with the declaration that “the thing about being the murdered [role] is you set the plot in motion.” Through this repetition, she calls attention to the murdered female cliché, uses it to build her collection, then turns it on its head, subverting murder mystery tropes and opening space for reflection.

Ulrich uses a second person point of view throughout, which is a bold choice and uncommon enough to invite speculation. Why write directly to the reader as “you”? For one thing, it demands our direct participation as a character in the story. In each flash piece we read, “you set the plot in motion.” We are the dead women, and Ulrich’s narrator is telling each of us what happens after we are gone.

This point of view gives Ulrich permission to almost completely ignore the details of the actual murders. After all, the murdered know who killed them and how it happened. They want to know what happens next, the parts they don’t get to be around for. But what I wanted to know was who did it, where, with what weapon, and all those other morbid details that get me holding my keys between my fingers like Wolverine’s claws when I walk to my car at night. That’s what we’re used to; that’s the adrenaline rush we’re looking for; that’s how this kind of story goes. Examine the crime scene, debate motive and opportunity, identify the killer, and hunt them down, dead or alive.

Ulrich doesn’t go there. Instead of gore, she offers humanity. In many cases, the bereft owe something to the murdered, like a new appreciation of life, or a successful career. But credit cannot be given to murdered women. They didn’t choose to die. They may “set the plot in motion,” but they are not included in the stories they begin. They are absent. They are dead. They are the ultimate characters without agency, assigned responsibility for all of the action, unable to influence any of it. Words are put into their mouths. They are lied about. They become goddesses and pickup lines. They are disrespected, with their legacies taken over by their enemies and their deaths exploited for personal gain. They are missed.

Ulrich’s text is laced with anger and outrage and bitter irony. She tackles moments of intense grief without flinching, and balances them within a kaleidoscope of poignant moments. Ghosts of You is intense, but not exhausting. Each piece is as unique as the murdered woman who starts it. Collectively, they challenge our treatment of the murdered woman.

Why do we want so badly to know who killed her, and where, and with what? Is that the most important part of the story? Is it acceptable that our twenty-first-century stories have normalized murder as a plot point? That we consider real, actual murder stories as prime-time entertainment? Have we traded human empathy for a morbid fascination with violence?

I don’t have answers, but I do have new criteria for what I watch on screen. If the opening sequence includes violence against a female character, I’m out. I’m tired—exhausted—of seeing bodies that look like mine functioning as anonymous plot points in someone else’s story. So, too, is Cathy Ulrich.

– Allison Wall