Exploring International Adoption through Fiction and Memoir: An Interview with Jessica O’Dwyer

By Diane Gottlieb

Posted on

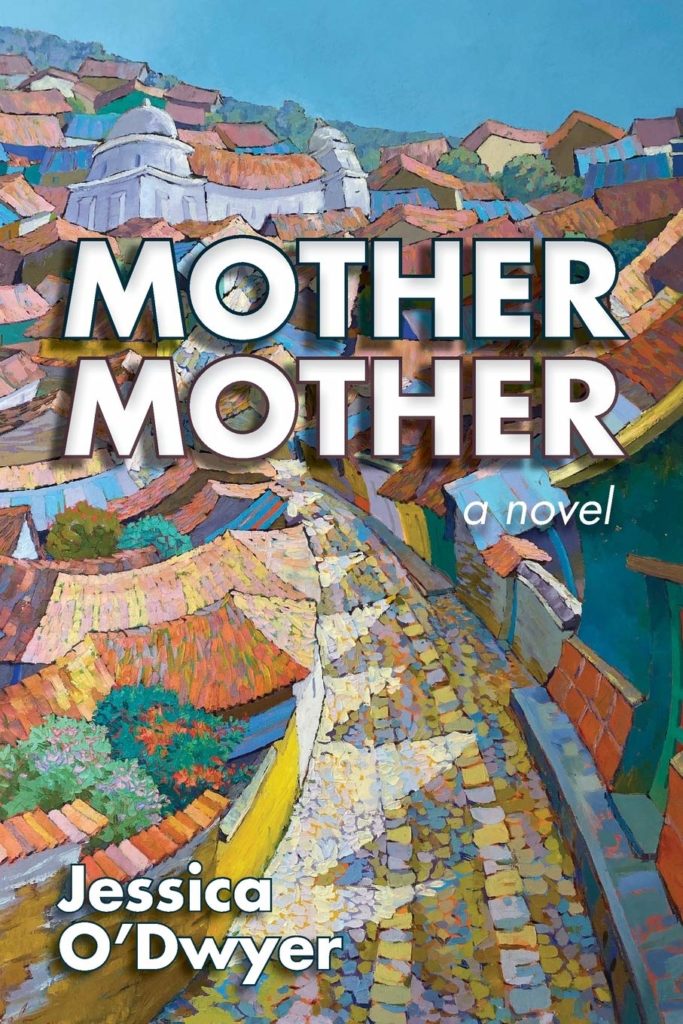

I met Jessica O’Dwyer when we were both MFA students at Antioch University in Los Angeles. I was immediately taken by her kind and giant heart—and her beautiful writing. I am not alone in my regard for Jessica and her work. Mother Mother: A Novel has received much deserved critical acclaim: it has been named the winner of the 2021 San Diego Book Association Awards in general fiction, a finalist of the 2021 National Indie Excellence Awards in general fiction, a Distinguished Favorite of the 2021 Independent Press Awards in women’s fiction and was awarded third place in the 2021 Feathered Quill Awards in literary fiction.

Mamalita: An Adoption Memoir, JessicaO’Dwyer’s powerful account of her family’s experience with international adoption, was named Winner of Best Memoir San Diego Book Publishing Awards in 2011 and one of the Top 5 Adoption Books by Adoptive Families Magazine in 2011. Jessica’s essays have been published in the New York Times online, San Francisco Chronicle, Scary Mommy, Grown & Flown, and Marin Independent Journal.

Jessica O’Dwyer has worked as a magazine staffer, museum publicist, and high school English teacher. She earned an MFA from Antioch Los Angeles. Jessica grew up at the Jersey shore, the daughter of a former Radio City Music Hall Rockette. She lives with her family in Northern California. I spoke with Jessica on Zoom about Mamalita and Mother Mother, the switch from memoir to fiction, her road to publication, and how her own life experience informs her understanding and writing about the complex subject of adoption, which she considers “the most profound story on earth.”

Thank you, so much, Jessica, for speaking with me today. Your two books center around adoption. The first, Mamalita, is a memoir of your family’s amazing adoption story.

It was quite a story, and I knew even as I was living it that I needed to write it. And I needed to write it not only for myself but for my children and for the children of other adoptive parents and for other adoptive parents. I felt that there was a mission larger than only myself.

You knew that even as you were living the experience?

Yes. Even as I was living the experience. I was always a writer and journal keeper. I was an English major in college. After I graduated, I moved to New York where I worked in book and magazine publishing for years, in production and PR. When I moved to California, I began editing the Members’ Magazine at the LA County Museum.

I kept very good notes during the adoption experience. If I had a conversation with someone, I would afterward take notes on it. I saved emails with our adoption agency, with the embassy, with other adoptive parents. So, I had a lot of primary source material. I wasn’t forming it into a book at that point, but I knew that what I was experiencing was important and I needed to remember it.

You lived what seems to me an adoption nightmare.

I think many adoptive parents say, in retrospect, “The nightmare was what we needed to go through to get to where we are.” That’s sometimes the way it is with life.

What I can’t believe is how uninformed and naïve I was. At the time, I didn’t understand the “adoption industry”—and I use that term carefully—or the culture of Guatemala. Now, I understand more about both.

I was working at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), and the adoption was dragging on and on. We visited frequently and realized the back and forth between my daughter Olivia’s foster mother and I were confusing for everyone. We agreed it would be best for Olivia to attach to one caregiver, and that caregiver was going to be me. I quit my job at SFMOMA, rented an apartment in Antigua, and moved there.

Everything that happened brought our family together, and it feels like the right family.

I can see that. And your experiences have brought you to writing these books which have helped many people.

I hope they have. They definitely have started conversations in our adoption community—especially about connecting with birth families. Mamalita was published ten years ago, and people still reach out to me to share experiences or ask questions.

After you wrote Mamalita, you switched to fiction and wrote your first novel, Mother Mother. What was behind that decision?

After Mamalita was published, I realized there was more to say about family, belonging, identity and marriage. I’d already told our story. The story I wanted to tell—needed to tell—was broader and deeper. The only way to get my arms around it was through fiction.

You tell the story through two protagonists: Julie, the white adoptive mother, and Rosalba, the indigenous Ixil Maya mother of Juan, the boy Julie adopts. How did you create the voice of a woman whose life is so different from your own?

Imagining other lives is the work of a fiction writer. That said, I did a ton of research. First, from visiting Guatemala every year and knowing my kids’ birth mothers as well as many other women in Guatemala. Second, from witnessing testimonials of survivors of Guatemala’s civil war. Third, I read everything I could get my hands on— Straight up political histories of Guatemala, diaries and letters in translation, guides for midwives and Peace Corps volunteers. I immersed myself in Guatemala and absorbed the information into my body, almost as an actor might. Then I sat down and put it on the page.

How does writing fiction compare with writing memoir?

With memoir, you lived the story. In fiction, you’re creating a world—characters, setting, narrative arc. I loved having to establish stakes, figure out the beats, get my characters into a room, have them change in some way, and get them out of the room. But the goal in both is the same: to keep readers turning the pages.

Writing Mother Mother was a labor of love—a long labor.

Exactly. I worked on it for seven years.

What’s it like writing a book for seven years?

The honest answer? Very isolating. Seven years is a complete cycle, a turnover. In those seven years, both my parents died, my kids went to five different schools.

Life happens and there are things you must do, want to do—for me, that was my kids and their well-being, my family and extended family. But almost everything else you say “no” to. I’ll give a shout-out to the Antioch MFA program here. They helped me cross the finish line. In the end, you have to be relentless.

And then there’s the road to publication! Can you share what that was like for you?

I pitched 90 literary agents. I always heard you needed to be rejected by 100 literary agents before going to plan B, which was to find a small press or self-publish. And, as you know, if you’ve ever pitched a book, pitching an agent is a careful process. It’s not doing an internet search for agents and sending out a form letter. You want to find an agent who has an interest in your subject or theme, or a connection to you, and you tailor your pitch specifically to them.

The agents who responded said, “You’re a talented writer, but this project isn’t for us.” After rejections from 90 agents—as I closed in on the magic number of 100—I started to pitch small presses that didn’t require a literary agent. And right away, Loyola University in Maryland said yes.

What do you hope readers take away from reading Mother Mother?

I wanted to tell a story about something essential—the lives of two women, the choices they made and had made for them, their transformations. I hope readers finish the book feeling like they know and understand the characters and have experienced something real. If someone’s beliefs or attitudes shift in some way from reading my novel—that would be a bonus.

– Diane Gottlieb