A Kind of Crooked Harmony: An Interview with Constantine Blintzios

By Patrick Parks

Posted on

Constantine Blintzios

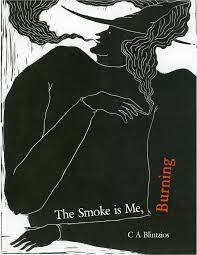

The Smoke is me, Burning by Constantine Blintzios, is the story of a family surviving on the edge of a pine forest in Harmswood, Arkansas. Crops have been corrupted by an outbreak of parasites in the rye. Livestock and buzzards alike are dying, so decay is left to spread unchecked. Blake and Jamie Ackerman have grown up on the lip of these woods. Raised by an alcoholic mother and a Vietnam-war veteran uncle, they have grown up believing in gods beyond the chicken-wire fence of their backyard, gods that steal children from their beds. When they are little, Jamie sees something in the woods and blinds his brother in one eye to keep him from seeing it, too. Though the two rely on each other for survival, they grow apart as they grow older. Blake gets away from Harmswood and goes to New York, but Jamie remains. Both continue to be haunted by their shared past, suffering in ways clarified by their surroundings, each finally facing the beasts that served the gods that had tormented them.

The Smoke is me, Burning continues the Southern Gothic tradition while re-imagining it at the same time. Themes made familiar by William Faulkner, Cormac McCarthy and William Gay run through the narrative, but they are transformed by Blintzios’ language and the singularity of his vision. From the first scene to the last, this is a compelling novel, one that will haunt a reader the way the gods haunt the ill-fated brothers.

Constantine Blintzios is a Greek/British writer. He has a background in music and Contemporary Art and holds an Mst in Creative Writing from the University of Oxford. He is primarily a writer of fiction with a focus on the lyric and its transformative qualities in prose. He has had poetry, short stories, and reviews published in journals such as Visual Verse, Ash magazine, Paris Lit-Up, the Oxonian Review, and the Literary Review. His poem ‘Where I am From’ was shortlisted for the 2017 Martin Starkie awards, he was long-listed for the 2019 DISQUIET fiction prize. As of 2021, his manuscript was longlisted for the Laxfield Literary Launch Prize. His debut novel: The Smoke is me, Burning will be published in 2022 by KERNPUNKT Press. He is currently studying for his Ph.D. in nightmare aesthetics at the University of Bristol.

You have said that your father’s having grown up in a small Greek village and losing sight in one eye “very much informed this book’s aesthetic and sensibility.” Could you elaborate a bit on that?

I grew up with the myth of my father losing sight in his eye. His childhood had an almost biblical quality to it. Even now, listening to him speak about it stirs me in very powerful ways. He grew up in a context where he remembers the electricity turning on for the first time, where he and his friends ran around chasing streetlights as they came on for the first time. His family had to travel down to the river on a donkey for drinking water. My grandfather’s house didn’t have a door for a time and manure was burned for fuel in the winter — all of this information is nourishing, beautiful, and important to me. It stirs up a kind of magic and reverie in my mind for a lived experience that feels so far from my own.

My father’s blinding is an event that has haunted him since he was very young but has also been entirely normalized. I sometimes forget that the color and quality of one of his eyes is completely different from the other. On the other hand; the color and quality of that eye is all I can think about on some days. Mysterious, like a half-moon. It was a privately traumatic event in his life that exists as an obvious manifestation of trauma for the entire world to observe — there is something in this paradox I find compelling. I have always been drawn to worlds that are hidden away. Of what a blind spot in a person’s life could suggest.

The brothers, Blake and Jamie, are both haunted–and maybe even hunted–by mythical beasts. Could you discuss the role of those unseen beings and, more generally, the prevalent superstitions in the story? What makes the siblings susceptible to the mysteries of the place?

My sprawling research included watching countless interviews of people who swore they had seen Sasquatch and the Tasmanian Tiger. Almost religiously. The deep haunting that plagued their memories, the conviction that this was a lived experience — that these extinct, unreal beings were somehow revealed to them alone, always in seclusion, intoxication or through a low-quality grainy photograph. There was a kind of magic there, on the tip of their tongues. I envied and reveled in that conviction.

The two brothers are misunderstood melancholics. They have both suffered in quite different ways which make their relationship with each other strange, estranged, and curiously codependent. Children have a tendency to think poetically and early memory is structured in a series of lyrical vignettes. Blake has managed to survive by losing himself in the words of others — dissociating himself from a very difficult and abusive domestic context and projecting his consciousness outwardly through living very much inside himself. Whereas Jamie’s experience is more alarming in the sense that he is exposed because he has witnessed dark secrets of the town from an early age. One brother looks away. The other stares the beast down.

The ‘Howlers’ are many things at once. I really wanted to stress this in the writing, that they are there as much in practice as they are in each person’s imagination. I tried to achieve a polyphony of dreamlike and hallucinogenic perspectives in order to open up these possibilities (even the idea that they may be a literal troupe of escaped chimpanzees that have colonized the mountains around Harmswood). I became increasingly interested in the nature of isolation and insular communities and the abstract qualities of superstition within those communities. How living on the periphery or a societal blind spot can warp the human mind. The Ozarks are so plagued with such obscure phantasmagorical folklore that it became a rich well to draw from in order to compose the timbre of Harmswood as a whole — but more specifically — to hone in on the darkness of family history and where these superstitions twist into malicious and abusive acts of justification, almost as expressions of intergenerational trauma.

There is something stereotypical about the way I have gone about expressing these aspects — in utilizing the Satanic Panic and rumor panic of the eighties and the gothic genre in general as forms of archetypes and exaggerated aesthetics. In a certain sense, I was interested in applying pressure to this stereotype, this familiar context of the backwoods, brutal hillbilly territory, and infusing it with something more complex and archaic — almost to layer it with eco-mythology. The space that exists between flesh and ether, between words and voice. Fluidity, the blurring of cognitive/sensory boundaries in the dark.

Of the mythical creatures in the book, Bald Knob the vulture is most present. How does this scavenger inform the narrative?

The necessity of a misunderstood animal is at the core of what both Blake and Jamie represent. The turkey-vulture became almost a coat of arms for the entire saga of this story. In the beginning, I used this symbol as a representation of the buzzard that tortures Prometheus, a dark form that punishes him for having stolen fire from Zeus in order to offer it to the people. This image guided me through the murk of the writing process. In one sense I wanted to invert the Promethean myth, in that the Bald-Knob is there for Blake as a means for the metaphorical devouring of his trauma, almost as a protective ‘familiar’. Like with Prometheus’s liver, this trauma always grows back until realized.

I was very excited by how the template of a classical myth could take shape in the backwoods of Arkansas. But beyond this, I became interested in the vulture itself, as a misunderstood creature. I looked into Towers of Silence in Zoroastrian religions, where bodies are placed on immaculate structures to be disposed of by carrion birds but also exist symbolically in the sense of excarnation — meaning the soul will literally be exhumed from the corpse and taken elsewhere by the birds. I became interested in the necessity of the vulture and its role in curating the circulation of a biosphere — of doing the dirty work and dealing with the worst parts of nature so that it may rejuvenate itself and flourish.

Let’s look at the setting, specifically at your comment regarding “the deep topography of backwoods, hinterlands and how history resonates.” Early in the novel, you describe through Blake the act of dressing down a buck. In that description, you state, “When the animal’s young you need to tug a little harder. Afterward, you’ll see all the maps hidden under the skin. Make the deepest cut across the horizon. It all needs to go.” Would it be fair to say that this action also applies to the way the people of Harmswood–at least the Ackermans–treat their young?

In short, yes. The way bodies, specifically animal bodies are treated and manipulated physically, is a direct representation of Harmswood’s homegrown, cultish folklore when it comes to their young and the ways in which they interpret their offspring. This idea of offerings to the wild. The setting both is and isn’t Arkansas; it is a nocturnal space with the potential for both nightmare and wonder.

I kept depicting bodies, animal bodies, almost as landscapes. The writing itself almost as a carcass, bones, chewy cartilage that sticks in the throat. Something indigestible and almost ruthless in its raw aspect. I did however feel that there was almost always, music and a lyrical quality that emerged from these scenes of disintegration and persistent brutality — a kind of gentler, inner yearning that seemed to synthesize quite naturally and it was in this space that my characters seemed to shape their voices; at that distorted cross-section of flesh and ether.

The ecological disaster in the book–the effects of parasites in the rye crop–adds to the area’s spiraling down. How does this fit in with your overall landscape?

This book is obsessed with decay and decomposition. A fear that brings decay. The ecological disaster of parasites in the rye and the gradual but very obvious decline of farmlands which have to keep being burned and reseeded was a strong mirroring of what was happening to my characters in the narrative. The hallucinogenic aspects of this decay were a link I was interested in teasing out, along with recent theories concerning witch trials — where ‘ergot’ (a parasite in rye) had certain properties that caused people (especially women) to hallucinate intensely and aid in their persecution. I played with the idea of parasites in crops and livestock directly informing the nocturnal folklore of the place, synthesizing superstition through what people thought they were seeing and hearing. In short, ecological disaster and family tragedy here are linked directly through those parasites in the rye.

Despite the novel taking place in a religiously conservative area, there’s no overt mention of church or church people. Do you see organized religion as having influence in the story?

There is an emphasis on God and what has become of that notion in a place like Harmswood. I was drawn to exploring ways of ‘undoing’ — what would it mean to undo a personality, a religion, a family. As organized religion, in my view, is a kind assault on and trapping of consciousness, I felt that its existence was there as a contextual given. At the same time I like the idea that, through the abandoned and marginal nature of place, organised religion has somehow been surpassed and replaced in Harmswood by a mongrel/bastardised version of spirituality that is entirely other. Having said that in terms of cultural/geographical context, the impact of organised religion has very directly informed the psychologies of my characters. In some ways the entire novel is an attempt to write the void that was once occupied by a God.

Although the novel settles into a more linear narrative, initially it seems to swirl and drift–smoke-like, if you’ll allow me the metaphor–and I’m wondering if you wrote the first part first or if that section came later and reflects your understanding of the characters once you knew how the story ends.

Everything happened beyond me. After a point, I felt like I had almost no control over what began to surface in the writing. This entire story started as a small spectral poem about the buzzard which circled and tortured Prometheus as he was chained to the rocks. In a way the novel in its entirety was approached in the same way I would approach a poem, for better or for worse, meaning line by line. Sentence by sentence. Language and its transcendent properties were far more important throughout this process than plot, other than the fact that I was keen for it to be realized in three parts. The pages burn slowly, but I feel that there is meaning weaved in at a molecular level — it just takes patience.

I am quite glad that the writing itself seems to come across as immersive in an almost physical way. I think it was a kind vessel I needed for manifestation and embodiment of both landscape and the souls that inhabit it. Almost a way of accessing specific emotional territories. But the idea is that everything is happening and being experienced through a veil of hallucination carried within the spores that glide through the air from burning sick crops.

In terms of storytelling, were the Blake sections always first-person and the Jamie sections third-person? How did you arrive at those points of view?

Jamie is more of a character sketch than Blake. His actions are more observed and described at a distance and I think I needed that. In some ways, Blake is quite hollow. He is more like the weather or a sounding board and everything happens through his murkiness. I needed there to be a clear distinction between the two of them for my own sanity if nothing else. It was a healthy way for me to understand and start expressing two separate minds and psychologies and make them into independent people because part of Blake’s voice is also entangled with my own as a narrator. So through various forms of experimentation, I arrived at this choice relatively early on in the process as a way of moving things forward. I created a kind of crooked harmony for the boys.

Your Native American character, Custer, is a major force in Jamie’s life. What drew you to him? War experience? Native American lore? His place in that society?

Custer grew very quickly as a character. Essentially he was sculpted out of a plethora of testimonies I read and listened to from survivors of the Catholic orphanages for First Nations children. In the same way that Vern was spawned from Vietnam Vet testimonies. The brutality in those stories was so transparent and abhorrent that Custer’s perspective had to be a cracked and yet strangely empathetic one. Custer is marginal and yet very powerful in his own way. For me, he is an example of something gone very wrong and his vengeance is justifiable for someone drenched in layers of unfairness. He reads Jamie’s pain easily when they meet. The fact that he ‘sees’ him is overwhelming at a point in Jamie’s life where he is at his most vulnerable. Custer becomes his cultish/psychedelic gateway into oblivion — a way out of a cyclical and wasteful existence. Ultimately this bond cultivates a blind loyalty that Jamie follows through to the end as one of Custer’s foot-soldiers.

When Blake leaves Harmswood and goes to the city, is he searching for something or merely looking for anonymity?

I think he is purely on the move. At least initially; he is following an arrow pointing in any opposite direction to Maw, Vern, and his blinding. The city is anonymous because it could be any urban context. I didn’t want it to have a specific identity or aesthetic. When he arrives there his life becomes primarily about repression of pain through intoxication and mundanity — the turkey-vulture grows huge in his mind. I really wanted to convey a kind of bird-bone hollowness to his every day, due to the fact that this internal shadow has become so prominent. In short, he is searching for anything other than home. Until he meets and bonds with Blue.

The bondage ritual taught to him by Blue becomes a release for Blake. How did you settle on this as a narrative device? In terms of the novel’s timeline, does the set-piece at the very beginning with the dancer actually happen or is it a manifestation of Blake’s freedom?

The Shibari tying technique was introduced to me through long conversations with a close friend who is a psychotherapist. We talked about the idea of holding and what that means for a person, and in her case, a client. The act of being tied up as a healing mechanism, a safe space, in which one can truly release whatever it is that haunts and pains them. My friend talked me through how she experiences rope-tying in its creative/therapeutic aspect and even took me to an event from which I was very inspired and turned into a segment of the novel. The poetics of someone being released or relieved through being physically entangled felt irresistible as a premise and something I was eager to explore through Blake as a vessel for both confronting his childhood wounds. In a literal sense, Blake’s psychological liberation through shibari mirrors the first scene of the novel where Wilf Batty is found hog-tied, dead, and hanging from the pines.

The image of the dancer at the start — for me — is something of an emotional crescendo. It illustrates a series of movements and actions that symbolise the trajectory of Blake’s trauma through a performative art form and is very much a manifestation of his transformation — a letting go of an all-consuming past. It is a visceral ode to life.

In addition to writing, you’re also a musician. How do those two artistic endeavors overlap? Or are they separate from one another?

I don’t think that they inform each other directly. But there is a certain sense in which I am always reaching for musicality in prose. Music is more visceral, instinctive, and effortless as an occurrence for me. It is my first love. Whereas writing, especially writing narrative, is quite taxing and painful at times to a point where I feel very inadequate. With music, I trust myself more because I have been doing it longer and there are fewer constructs to consider. Essentially both forms are born of an overwhelmingly lyrical sensibility that bleeds into everything I do.

Thanks, Constantine.

– Patrick Parks