Not Your Grandma’s Social Media

By Amy Kielmeyer

Posted on

My grandmother’s refrigerator door was my first experience with a social media page. She’s had a few refrigerators before and since the one I remember best, but they are all the same. While they are intended to keep food cold, their (only barely) secondary function is to hold the most recent photos of our current family members and a couple old favorites of some who are gone. Six Degrees is an easy game to play on her fridge, and I played it often as a child.

Grandma tends to her page regularly. Sometimes individual pictures stay for years, but then sometimes they switch out in just a couple of weeks. It all depends on how quickly others are sharing their photos with her. Add to that, the fact that only certain kinds of photos make it on the fridge. There are no school or graduation photos – they’re on a shelf in the living room. There are no wedding or church photos, either, those are above the fire place, on the wall, or in their rightful albums.

The refrigerator is reserved for candid shots, big successes, family photos that are not Christmas cards (those go in a stack she can carry in her purse), and carefully posed photos of people or small groups smiling next to something beautiful. It’s the difference between a class photo and the one someone snaps as you walk out the door for your first day of school. There is a photo of my grandma’s brother standing next to the Muskie he caught that’s as big as he is, one of my grandpa smiling well before he died of cancer, one of my cousin the day she got her braces off, a “sisters” photo of my aunts, grandma in a greenhouse surrounded by poinsettias, and a dozen other photos like them. All these years, every time I’ve gone to her fridge, I’ve been keeping up to date with my family.

The discovery that the refrigerator door could have a second, mixed-media function came, like many new technologies – memory foam, cochlear implants, and the Super Soaker – from an invention designed to drive space exploration. According to the Classic Magnets website, Sam Hardcastle, an inventor and mold-maker, was approached by the Space Industry in the late-60’s to make letters and numbers to slide along tracking charts. They would eventually need these letters and numbers to come in various sizes and colors, so once Hardcastle had found the right manufacturing processes, he started thinking about how he might use these magnets in other areas like advertising and collectibles. The refrigerator magnet was born, and for generations we’ve been hanging our grocery lists, photographs, postcards, and children’s art where every member of the household is sure to visit.

As with every good story though, there’s a hitch in that narrative. While Hardcastle does seem to have perfected the metal infused magnet that would become Classic Magnets, there are several competing histories. Many websites proclaim the first fridge magnet was patented by William Zimmerman of St. Louis in the 1970s, but that information, originally from Wikipedia, has since been taken down, and can’t be corroborated after looking through the records of magnet patents, which is now conveniently offered by Google.

This video, made by librarian Dr. Derek J. Ripley, claims that a shipwreck and failed pound shop led Emmanuel Shiverofski to design advertising magnets for trains, and in the 1870s, to team up with William Gladstone Blunt, who then adapted his designs for refrigerators. By the time domestic refrigerators became popular in the 1920s, the pair had 20,000 designs ready to go. Ripley’s story even has fridge magnets being rationed during WWII and used for propaganda in the US and Germany, which is still well before the other claimed “beginnings.”

All these versions are probably true: Shiverofski and Blunt first started using magnets for advertising, Hardcastle made a better, stronger magnet, and Zimmerman patented the idea of a decorative refrigerator magnet. The magnet is what makes the refrigerator door a page. Without the magnet, the door is just a surface, but the magnet turned the surface into a medium, a platform. I wanted to give the facilitator of that transformation some credit, but as we can see, that is not so easy, and maybe the complexity is better.

I had the privilege of spending so much time at my grandma’s fridge because we always lived close by. Where most of my cousins would visit for a week or two in the summer, my little sister and I were there most weeks to mow the lawn, pick beans, go fishing, or play cards. Even more, my mom and I lived with my grandparents until I was two. I don’t remember that time exactly, but if I trace it back from spending hundreds of dollars on DNA tests and ancestry website memberships, to laying on a waterbed looking at photo albums pulled from dusty drawers, to spending every church service looking at little homemade albums of animals cut from the covers of greeting cards, to photos of us reading books in her bed, to this one of us sitting together looking at a photo album, I am certain she taught me to read images as artifacts – to see them as the stuff of life.

My grandmother’s house is a decades-in-the-making display of her life, and her fridge is her Instagram page. But what makes it social media, and not a museum, is the degree to which what gets posted relies on others having shared it with my grandma in the first place. Everyone in our family knows to tell Grandma, whatever it is. She talks to everyone and is a virtual voice recorder of facts, with only occasional interruptions of analysis or measures of value. This is important because it ensures that everyone continues to want to relay information to her. My grandma is very religious, and while her strong morals have grown more accommodating over the years, whether she knows it or not, she is a master of self-inflicted disappointment. I don’t know if she’s ever actually been disappointed in me, but I know for sure when I have been disappointed in myself for her.

If this was all she was though, no one would tell her anything. And yet, my grandma is on everyone’s most contacted list. I tell myself that it’s because they all really want to be on her fridge, but it is not so easy, and maybe complexity is better. My grandma is our family’s refrigerator magnet, because she made our relationships dynamic and interactive. She took each of our doors and turned them into mediums, platforms. We all connect and pass our lives on to each other through Grandma. Her house or wherever she is, is the refrigerator. She is the display of all our work out in the world, and if we share it with her, she wants everyone to see it. When something important happens, you’re supposed to tell Grandma, and then I go to Grandma and I look at her fridge, and Grandma tells me.

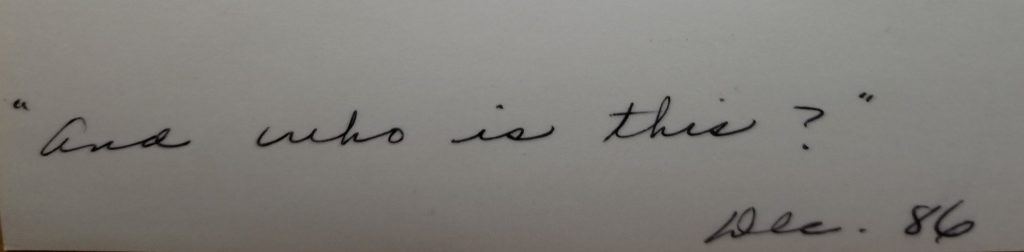

In all honesty, she probably tells a lot of people about her family, but in our relationship, I am the listener and she is the teller. I always listen to her, and better still, I egg her on. Tell me more, I say. “And who is this,” I ask. She sits in her chair with her eyes closed while I toss questions about everyone who has a new photo, or anyone who’s photo I’ve noticed has been swapped out. I wonder where those photos go. And while I sometimes worry about them, I know that my grandma is a meticulous recorder and would never abandon the record. It’s just that I’m sentimental, and even the long streak across the front of the fridge where my grandpa brushed against the door with a pencil in his pocket is a part of the record, and most people will just rub that away.

My grandma is 86 years old, walks two miles most days, and has a Life Alert. I’ve been preparing myself for her death for half my life, because I am certain I will never be ready. The way I look at the stuff of life is because of her, and the only engagement my family has is because of her, and I worry where we’ll all go when she is gone. I used to complain to my mother because only a few of us seemed concerned with building lasting relationships; because the internet, and Facebook, and text messages are not the same as holding the thing and having my grandma tell me about the person.

As we’ve seen with good stories though, this is not the only narrative. While it might be true, it’s unfair to rely solely on the work she has done to build strong bonds with her family as the justification for my own strong bonds. I am just as guilty as everyone else, because I’ve never told them how often I stood looking at their photos, and I never considered that looking and studying and asking her questions about them wasn’t enough to actually connect with them. I was connecting with her.

What I didn’t see, is that my grandma is present in all our lives, but differently. What makes her special, or in this case – social – is not that she has a fridge, or that she might put someone on her fridge, but that whoever sends her photos wants to be present in her life. They want to be present in her life because she is present in theirs and she has created positive connections. My grandma never stood gazing at someone else’s refrigerator imagining whatever life she could from the details of the photos; stowing those memories away for later recall and pretending they were real connections. She called them on the phone, or wrote them a letter, or drove to their house. She added them as a friend.

– Amy Kielmeyer