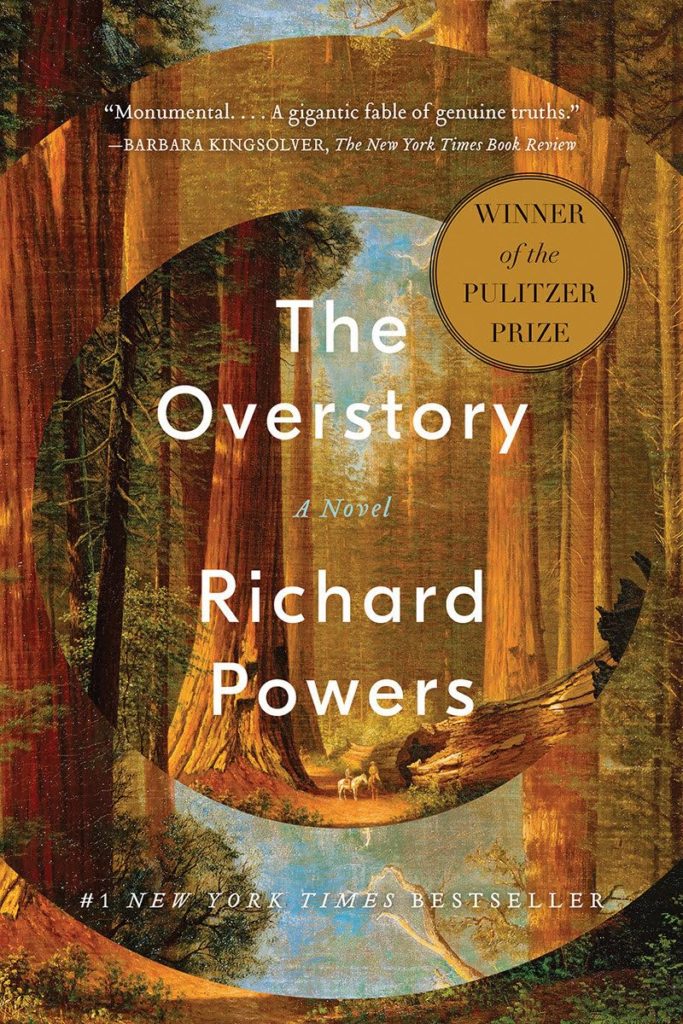

On ‘The Overstory’ by Richard Powers

By Tara Awate

Posted on

In most novels that have beautiful nature writing, nature only acts as a backdrop, a pretty painting and landscape to hold the real stories between people. I’d be spellbound reading those well-drawn details of beauty, of peace and green and spring. But The Overstory by Richard Powers takes it to another level, making those descriptions seem inadequate and superficial for something so grand and miraculous: trees. In response to the Overstory, the trees would say to the Romantic poets– Shelley, Byron, Keats, “You only like me for my looks? Nothing else?” Powers gives us that something else. He illuminates for us their history, biology, personifies their desires, fears, hopes, and very soul, beyond merely their commercial or aesthetic appeal. It brings forth the forest as an alive, dynamic system that’s buzzing with life and its own dramas at every moment, inside and underground.

Though immovable, trees are doers throughout the story. The story is rife with paragraphs and scenes where the characters are doing nothing but roaming through a forest. And it’s still compelling. While reading, I was made wholly aware of all that’s going on around, in the soil the trees stand upon, their branches, cells, roots and insects they depend upon. It never turns into jargon and it felt like I was getting to know a long-lost family member for the first time, intimately. I was invested; conscious when in a wild space, like the forest is conscious, attuned to everything around it. Not a mute, stationary thing. Even when we’re just standing doing nothing in the forest, nothing around us is static.

In the novel, people are at the periphery, and the inanimate forest in the backdrop has assumed the role of the protagonist. This naturally demands an antagonist or at least an anti-hero, which end up being people.

Since their childhood, all of the characters have existed in a slight exile from human society. They’re a bit off-kilter, not fully assimilated into the social structures around them. For some, it’s due to a concrete thing that prevents them from doing so like being paraplegic, being resurrected from death or an accident that leads to a lifelong coma. For others it’s a mere expression of their personality and a result of their circumstances. One high school student’s unquenchable scientific curiosity makes him out of step with the other kids, working alone on experiments no one cares about; a war veteran is scarred by his crewmates’ deaths and lives alone on a ranch; a hearing-impaired young girl cannot fully connect at school and spends most of her time frolicking in the woods with her father; a man in rural Iowa whose ancestors recorded the growing up of a hundred-year-old tree, to form a time-lapse and he yearns to preserve that legacy. They all come together united for this one purpose: saving trees. They go to extreme lengths for this, even resorting to eco-terrorism.

The drama of the characters themselves is sparse and there’s very little to almost no spice in it. They are half here half there, in that other, greener world. In the end, to enter and fully inhabit that world, they inadvertently exit the human one, renouncing all its laws to listen to older, more benevolent ones. Without exiting it, they couldn’t hear those lower, subtler frequencies the forest communicated in, subdued by the louder, faster frequencies that the civilized world ran on. And they do so gladly– for they feel they have stumbled upon God, in the most overlooked place, in the most unlikely of forms. A god that induces wonder, has intention, someone who has been here since time immemorial. And the quest to preserve the magic they have discovered is fraught with civil disobedience, violence and death. Their journey is so full of wonder and chance encounters, you want to ride along on their thoughts and experiences.

The Overstory is brilliantly researched and accurate down to the tiniest of details, drawing from a wide range of sources. It’s mainly set in the 80’s and 90’s when the Ecopsychology movement was taking root. It was during the same time period that the tome Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind by Theodore Roszak was published; it brought together shamans, naturalists, entomologists, psychologists, primatologists, engineers to contribute their insights and experiences on the topic. I felt The Overstory fictionalized that and attempted to achieve something similar. There’s a character (Patricia Westerford) that heavily resembles Rachel Carson and I’d like to think that it’s an homage to her.

The omniscient narrator once imagines New York City in its entirety turning into a sprawling jungle, the landscape reverting back to its original state– the way it was many millennia ago. The 2008 novel, “The World Without Us” answers that hypothetical question: if all people were to disappear from the face of the earth tomorrow—as though from a single click of a mouse that erases all the players, leaving no corpses or vestiges except everything we have ever created: offices, houses, buildings, bridges, roads—what would happen? In over a few hundred years, it would all be subsumed by the forest; swallowed.

This post-apocalyptic vision might be chilling and unwanted by most but to Powers it’s not. The novel is unabashed in its stance about man vs wild: Neither can live while the other survives. It’s fiercely, unapologetically idealistic. Though I didn’t agree with all of it, it willed me to revive a bit of my own enraptured, doe-eyed idealism about nature and conservation that had worn away over the years by rationalization.

It had first started when I stumbled upon a copy of Walden in eighth grade. I was only drawn because of one thing: Thoreau and I shared the same birthday. That seemed portentous to me. When I first read about him, I perceived him to be a misanthrope. It seemed to me that he preached a hermetic existence, shunned human society and wanted to escape life. Afterall, he removed himself from everything to go live in an isolated cabin in the woods for two years. That sort of radicalism appealed to me as a highly rebellious thirteen-year-old. I clung to that myth of him for a while.

I didn’t really power through the dense 19th century English of Walden that time but I leafed through excerpts of Thoreau’s work and other Transcendentalists: Emerson and Walt Whitman. The natural world was personified in my mind and became Nature with a capital n. The Overstory revived in me that long-lost forgotten feeling. It never felt preachy and I was drawn in while the book asserted a singular resonating message throughout: You’re a part of something bigger and transcendent. All you’ve to do is bow to it and you’ll be saved. That is, if you’re not too late.

The narrator is very specific, and talks about every single tree so meticulously, where it grows, how it reproduces, how long it lives, how it interacts with other trees like they’re his own children.

Because the topic is indirectly being talked about as a religion, and there are cults around it, there is some didacticism that can’t be avoided. But it never feels forced. The unrestrained reverence of trees is almost spiritual and the characters at many times ‘lose’ themselves in it– transcend their physical realities to enter an expansive state full of purpose and light.

*****

Two summers ago I worked on a sugarcane farm in the Indian countryside. On all sides I was flanked by acres and acres of fields and orchards. It was harvest season for a lot of crops and many bullock-carts were filled with nuts, fruits and grains.

I met the farmer and we got to work in the sugarcane field, the saccharine smell permeating the air. He told me how much crop they had lost to last year’s flood. This year the rains are on our side, he says. We’ve been blessed with such a bounty. No telling what next year might bring. It struck me, the uncertainty with which these farmers lived. A simplistic hand to mouth existence. And yet, so grateful. We toiled in the field for two hours until his wife called, saying lunch was ready. As I walked back to the hut, Vivaldi’s ‘Storm’ from Summer began playing in my head. The dramatic arrival of thunder, then rain and then the storm as people scurried indoors, taking with them the clothes they’d put out to dry. I like to think that’s what Vivaldi imagined three hundred years ago when he composed it; that my feet are on the same ground that existed then.

His wife was roasting a roti on a smoldering charcoal stove with wooden logs underneath, making it fluffy and full of hot steam that escaped from a tear on its side. She served it to me on a plate made of a huge banana leaf, her hands caked with flour. The food was earthy and filling.

The farmer didn’t bother himself with the lofty, philosophical ideas of transcendence through nature and the bigger societal questions Thoreau posed through it. He was practical and grounded, with little connection to them. Simply appreciative of the earth that gave him a livelihood. The things they use to make their home were directly extracted from the forests. And most times, I could easily trace and know where in the natural world they came from. The broom whose bristles were made directly from a coconut tree’s leaves. The floor in their house was smeared with dried cakes of cow dung. It kept the house cool in the hot summers. They owned a kerosene lamp, the first one I’d ever seen. Many of their pots and utensils were made of mud. The objects that made up my apartment in the city, if I was asked how exactly they were produced or what their constituents were and where they came from, I wouldn’t be able to say. They’re factory made and highly refined, their final forms very different from their original constituents in their raw state. They look very removed from where they came from. Artificial. I’m not at all a Luddite but this could be something to consider and think about. The farmers and tribal people are directly dependent on natural resources. They have to bend and bow to its whims. They don’t exercise supreme control over nature. This somehow instills in them a respect toward it: seeing themselves as part of the ecosystem, not masters of it.

– Tara Awate