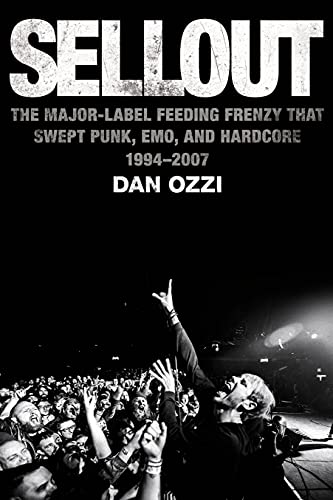

If you want to be a working artist, you have to sell art: a review of ‘Sellout’ by Dan Ozzi

By Samantha Rauer

Posted on

Perhaps no one has phrased this better than Michael Burkett, also known as “Fat Mike,” the lead singer of NOFX and co-founder of the San Francisco-based indie label Fat Wreck Chords. “I signed a fucking band; I didn’t sign an artist!” Fat Mike is quoted as saying in the last chapter of Dan Ozzi’s book Sellout: The Major-Label Feeding Frenzy that Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore (1994-2007).

“If I’m gonna give you hundreds of thousands of dollars, help me sell the fucking records!” The punk singer and businessman is describing his frustration with Against Me! (the Florida band known for songs like Sink, Florida, Sink and Baby, I’m an Anarchist!) and their choice of album artwork for Former Clarity, featuring a black and white photograph of a single palm tree, which according to Fat Mike, was not a cover that would sell records.

Sellout follows an arc, tracing the entire swell of the pop punk and emo wave during the late 90s and 2000s, taking the reader from Green Day opening for Operation Ivy in Oakland at the legendary straight edge venue 924 Gilman Street, through skate parks and Blink 182 streaking through LA, to Alternative Press covers, the MySpace era, and the re-election of George W. Bush. For a generation, this was the music we were raised on.

Emo nostalgia is not new (see Jia Tolentino’s piece on Emo Nite for the New Yorker on this topic), and anyone born between the mid-80s and early 90s will find many satisfactory “Yes!” moments in this book. For me, it was Thursday opening for Saves the Day at El Corazon, a now-defunct venue in Seattle where you used to be able to smoke cigarettes inside and buy cheap merch, and Rise Against’s unlikely breakaway acoustic hit Swing Life Away becoming the soundtrack to senior years across the country.

By the time I was burning illicit mix CDs in high school, At The Drive-In and Jawbreaker (both featured in Sellout) had already broken up and were frequently cited as musical influences by the next generation of bands to be slapped with the emo label. My memories of Warped Tour soundtracks and checkerboard Vans peak somewhere around the time when Ozzi writes about the Donnas playing TRL in 2003 for Spankin’ New Bands Week, alongside Good Charlotte, New Found Glory, Simple Plan, and the Used.

The Donnas are the only all-female band featured in Sellout, although other chapters are dedicated to the Distillers’ 2003 Coral Fang release and the 2007 album New Wave by Against Me, which is the chapter that quotes Fat Mike and describes the rise to stardom of transgender frontwoman Laura Jean Grace with a heartfelt empathy that is afforded to all of Ozzi’s subjects. (Ozzi previously co-wrote Tranny: Confessions of Punk Rock’s Most Infamous Anarchist Sellout with Laura Jane Grace, which was listed on Billboard’s list of The 100 Greatest Music Books of All Time.)

Ozzie strikes an impressive and delicate balance between humanizing the bands he writes about and highlighting their artistry while, on the other hand, documenting the industry machine of the “majors” that preyed on them and promised studio budgets and bountiful paychecks. A creative industry will always need talent – in this case, the people who wrote the hooks, played the instruments, and performed on stage, and while a budget can help, it does not always guarantee that a group of humans in a room will create a commercial hit.

Money, by itself, does not create sellable art. To be fair, some of the A&R representatives were fans and visionaries in their own right, scouring basement clubs and advocating for unknown artists, like the late Craig Aaronson who signed the likes of Jimmy Eat World, My Chemical Romance, and Taking Back Sunday. However, accounts of label executives accustomed to courting musicians with strip clubs trying to win over underage skateboarders and comic book nerds, paint an entertaining picture of the frenzy.

Many of the musicians signed were very young – not much older than I was when their songs first resonated over headphones. These were bands of teenagers, or at the most, twenty-somethings, making the leap into the mainstream. Bands who often just wanted to write songs about girls had no option but to sign. It was that or stop making music because they didn’t have enough money to purchase gas for their tour vans. Chapters include the signing of the eager, clean-cut members of Jimmy Eat World, who were dropped from Capital Records in 1999 after two albums, only to go on to self-record Bleed American, and the early aughts rise of My Chemical Romance, the band of weirdo Britpop influenced underdogs whose loyal MCRmy I can’t help but compare to the BTS Army of equally obsessive K-pop fans.

Jawbreaker, one of the earliest examples of the sensitive confessional style that would eventually be labeled “emo,” originated while its members were NYU students. Jimmy Eat World hails from Mesa, Arizona, a city in Maricopa County, where locals were proud of the mainstream breakthrough of their hometown boys. Even the origin stories of groups that are now forever tied to pop culture and advertising, like Green Day and Blink 182, are in a way touching. No one is born a rock star.

In the case of At the Drive-In, who adamantly dreamed of signing to labels like Kill Rock Stars or Dischord, selling out ended up being their only option after the punk labels didn’t want them. The independent scene was, as it always was, the cool scene, as well as the most pretentious one, and the most difficult to break into. Needless to say, “selling out” didn’t always earn bands a lot of friends, especially with the purists. The DIY punk ethos, which originated in the 1970s punk rock explosion, was still alive despite growing mainstream interest.

However, if the UK wave had been rooted in anti-establishment politics, the pop punk and emo wave of the 1990s was largely a creation of record labels, looking for the next underground scene to exploit. The backlash is particularly evident in Ozzi’s description of the Bay Area community surrounding Gilman Street and the influential zine Maximum Rocknroll. After signing to Reprise, Green Day was banned from playing at Gilman and the Dead Kennedys frontman Jello Biafra of the Dead Kennedys was allegedly kicked in the head there, as a surrounding crowd yelled ”sellout” and “rich rock star.”

Ozzi does pay respect to independent labels throughout Sellout, with enough knowledge to demonstrate savviness, describing the loyal punk rock mafia surrounding Epitaph Records and Rancid’s Tim Armstrong, and going into depth about the bullish reputation of Victory Records founder Tony Brummel. I suspect there could be another book about distribution deals and punk imprints and acquisitions, such as Vagrant and Fueled by Ramen, which is one hole in Ozzi’s narrative that left me curious for more.

Another missing piece of this story is a deep dive into the deals that the bands were given by the major labels, and how much they ultimately earned by cashing out. Ozzi alludes to some bands receiving larger signing bonuses and tour budgets, and the treatment of bands by their labels is revealing, with some labels letting bands out of their contracts early when popular tastes had changed or bands had not performed as lucratively as the label had hoped. The details of the contracts are not explored in detail, perhaps to keep the focus on the bands and their individual trajectories, rather than to examine the exploitative aspects of the music industry as a whole.

Sellout drops us in the year 2007, with the acknowledgment that the industry was undergoing rapid change. As Ozzi describes, the rise of the internet and illegal downloading had started to turn the business of music upside down. Sony and BMG merged in 2004, and EMI was eventually purchased by Universal in 2012, leaving Universal, Warner, and Sony BMG as the remaining Big Three that still exist today. Spotify and streaming services now dominate music consumption and ‘360 Deals’, where labels own a portion of an artist’s entire revenue, not just album sales, is one way the corporate world has evolved in response.

It is no secret, either, that musicians continue to be taken advantage of by unfavorable recording deals. Taylor Swift’s dispute with Scooter Braun and Big Machine Records over the ownership of her masters was widely publicized and Swift was backed by politicians, Swifties, and the entertainment industry alike. Jeff Rosenstock of Bomb the Music Industry! has been a leader in the new digital age, founding Quote Unquote Records, an online donation-based label. Still, in a time when bedroom recordings can earn enough online viewers, profit, and fans to attract the interest of the industry, it’s yet to be seen if the lure of selling out will ever become truly obsolete.

The pop-punk craze of the 2000s was a golden moment for the music industry, when customers like me still purchased albums in the aisles of Best Buy but were increasingly using websites and illicit downloads to discover new and old music alike. Reading about record label boardrooms and bidding wars makes one nostalgic for simpler times, if only because it represents a time when A&R had to travel to see live shows, and the experience of music for everyone was perhaps something more tangible and physical.

– Samantha Rauer